All That Remains

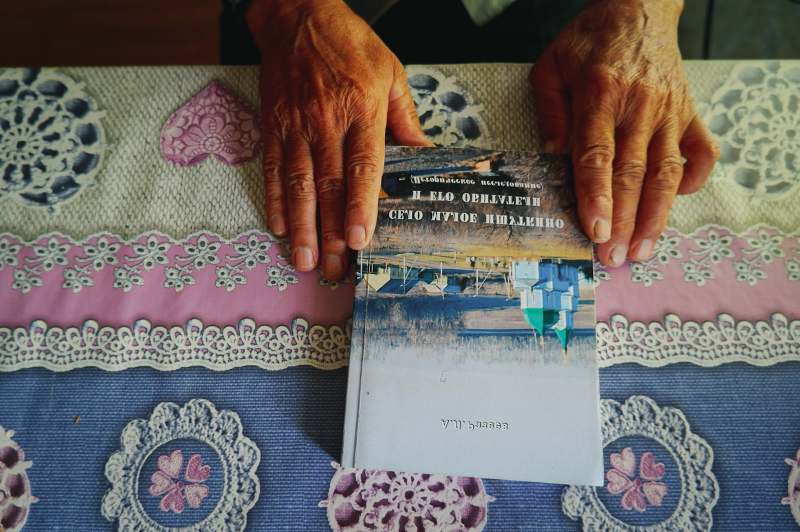

Seventy-eight-year-old Alexander Razeyev spent five years in the archives, piecing together the history of his native village, Maloye Ishutkino. He traced his own family lineage back to 1667 and then explored the family histories of the rest of the village’s current residents. The retiree organized his findings into chapters and told the story of Maloye Ishutkino in the best literary language he knew how. And then, at the end of 2019, he published The Village of Maloye Ishutkino and its Residents. He thought people would be welcome his work. They did not. Apparently, not everyone likes to reflect on the past, and many would simply prefer to close their eyes to their own family history.

The Collective Farmer

Maloye Ishutkino, population 217, is a tiny Chuvash village in Samara Oblast. Before Alexander Lukich Razeyev* became interested in its history, there was basically no easily available information about it.

Alexander Lukich and his wife Irina live in a small home across the street from the ancient Church of the Archangel Michael. A long chapter in Razeyev’s book is devoted to the church.

Snow white hens bandy about the Razeyevs’ irreproachably tidy yard. The home has well-scrubbed floors, and the mirror and television have been covered with white tablecloths. Two weeks ago in Moscow, for reasons as yet unknown, their son Alexander passed away. Irina’s eyes are swollen shut from crying, but Alexander is holding it together.

We go for a walk. Any stroll through this village would be short. There is just one central street nestled among hills. As a first order of business, Lukich takes me to the cemetery. His ancestors are buried there, and at the cemetery’s entrance is the fresh grave of his son. Fingering the wreaths on Alexander’s grave, sent by friends from all over the country and the world, Lukich smiles guiltily, and admits that, before his son’s death, he had no idea he had so many friends.

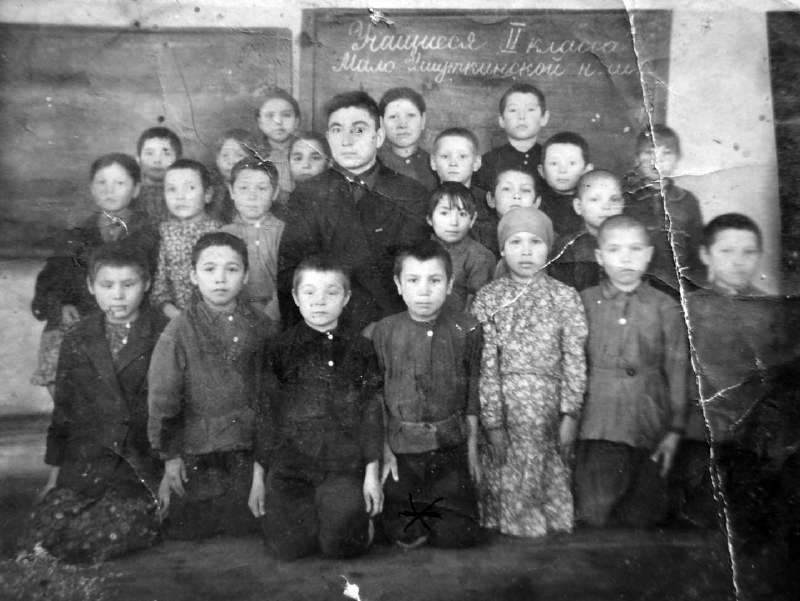

Razeyev does not consider himself to be either a writer or a historian. “I’m a simple collective farmer,” he said, swallowing the l in the word kolkhoznik. “Life was like it was for many in those times: school, agrotechnical college, and the army – I was an aviation mechanic. I was a good student in school, and they recommended me to an institute in Samara, but my parents wouldn’t let me go. Just like me, they were collective farmers. We were poor; we had to work. I don’t even remember whether I ever dreamed of a profession.”

Razeyev has loved literature and history since he was a boy in grade school, yet life did not give him the opportunity to pursue those subjects in greater depth. After serving in the army, he returned home and began the difficult work of a mechanic on a collective farm. Occasionally, out of curiosity, he would pepper the old folks with questions: Who was Ishutka? Why is the village named after him? How did the village church survive in the 1930s, when all the churches in surrounding villages were destroyed? But that was the extent of his historical research. “By the time I became seriously interested,” he said, “many of the old-timers were gone. It’s such a shame that we didn’t listen to the old folks’ stories when they were still alive; we just weren’t interested.”

In 1983, Lukich, his wife, and their five children moved to Novospassky, a settlement in another district. There he got a job in a new state farm, much larger than the kolkhoz where he had been working. Back in Maloye Ishutkino, he and his wife had had a modest home without any indoor plumbing, their children walked five kilometers to school, and Razeyev had to trudge the same distance to work every day.

Novospassky, on the other hand, offered civilization: asphalt, an apartment with running water, school, a kindergarten, a personal car with driver – a life of luxury.

“During my interview, the director of the state farm asked, “Can you install angle sprockets on the manure conveyor?”

“Yes, I can do everything with my own two hands,” I replied.

“That’s it, you’re hired!”

The Razeyevs lived in their Novospassky paradise until they retired. Then they returned to Maloye Ishutkino.

“By that time, the kids had all scattered, and my wife and I were left with a four-room apartment. What, were we supposed to play hide and seek there?” Razeyev asked. “It was after retirement that I developed a passion for history.”

The Call of the Ancestors

Lukich would occasionally see historical notes about neighboring villages in rural newspapers: “When they were founded and by whom, how they developed, what sorts of historical relics had survived, how people lived during the war – that sort of thing. So I thought, ‘What do I know about my own village?’ I went around bothering our old folks, and I wrote my first book based on their stories. Yet their facts would conflict: someone, for example, said that the name Ishutka was Chuvash, someone else said he was Mordvin. There was a lot that the old people didn’t know, there were many inaccuracies. So, not finding any official dates or information anywhere, I decided to go to the archive in Samara.”

Razeyev did not know how to work in the archives. He simply showed up and said that he was an interested resident who wanted to learn more about his village. The archive staff guided him, and Lukich dove into the documents. He emerged only a week later.

From that visit, his first, Razeyev returned with the fact that Ishutka was actually Chuvash (in one fell swoop dispensing with the long dispute between local Chuvash and Mordvin residents). He also clarified the name of the town’s first priest, and dug up all sorts of other pieces of information.

In awe at the quantity of unknown and interesting facts that were preserved in the archive, Lukich soon returned to Samara. And there they told him about the existence of the church register, through which he would be able to study the history of his family.

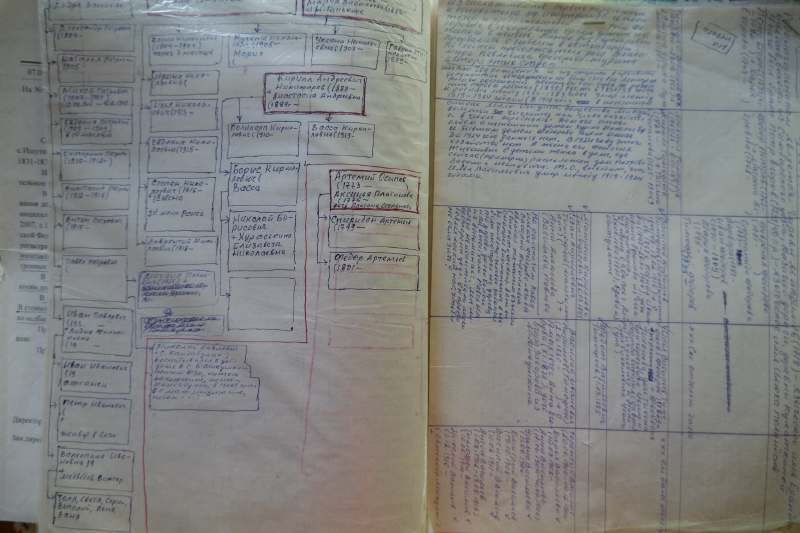

“I dove in and, searched for my ancestors, beginning with my father and grandfather,” he recalled. “And I dug deeper and deeper. I excavated all the way back to the 1600s. I reconstructed the Razeyev family tree. Then I started searching for other village families. And, thanks to the register, I traced the family names of all the residents of Maloye Ishutkino, going all the way back to 1762. Who was born or died when, and who they married and where they were from.”

After exhausting the resources of the Samara archive (he has no idea how many times he traveled there), Razeyev set out for Orenburg. “Our village has been a part of Samara Province [gubernia] since 1861,” he noted. “Before that, this was Orenburg Province. Their archive therefore might also have some important information about our village. That drew me like a narcotic. I just wanted to know as much as possible.”

Razeyev didn’t know anyone in Orenburg, and he didn’t have any money for a hotel. So he slept in the train station. “I’d wake up in the morning and walk to the archive,” he said. “In the evening, I returned to the station – and that’s how I spent a week there. I found so much information! I learned how the province was divided up into districts and volosts.* Of course, you can’t hunt down everything in a week, plus I was copying everything down by hand, and that takes a long time. So I returned there again later.”

News of Lukich’s avocation spread through the village, and when he headed to Orenburg for the second time, the local priest gave him a thousand rubles for traveling expenses. Meanwhile, Razeyev recalled an acquaintance he had in Orenburg. He dug up the contact information and gave him a call. The acquaintance promised to take care of Lukich on his next visit and put him up in a hostel. And he paid for it. “He helped me as if we were fellow villagers,” Lukich recalled happily.

After Orenburg, Razeyev traveled to the archive in Kazan. There, he paid his own lodging at a hostel. Then he traveled to Moscow, where his son Alexander welcomed him, put him up, and helped him get around. That was followed by another trip to Samara…

The archive trips put a serious dent in the retirees’ budget, so they saved money wherever they could. Much of the information Razeyev sought exists in open sources, accessible via the internet. So, to minimize his travel expenses, his children gave him a laptop computer and internet access. The 75-year-old (at the time) Razeyev learned his way around the internet and perfected single-finger-style typing. Things definitely got easier, but he didn’t stop visiting the archives. Meanwhile, his wife Irina never objected to his hobby, in fact she encouraged it. “It’s a good thing,” she said. “After all, we found out about our ancestors!”

“I even found a few relatives!” Lukich exclaimed. “There’s an infectious disease specialist working in the Isakly Regional Hospital. He became interested in the book and asked me to send him a copy. I took one to him and he said that his relatives were born in our village. I asked their last name, opened my documents, the church register, and found out that they were Razeyevs. I told him: “You and I, we are relatives, can you imagine?”

“And there was another case with a close friend. We had been friends from childhood until his death. And it turns out that we too were relatives. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a chance to tell him that before he died.”

No Money, Yet Still You Write

After many years of work (Lukich painstakingly transcribed and copied out by hand everything that had anything to do with his village and its residents), the kolkhoznik had collected in his home the most detailed archive imaginable on his native village. The contents of his second book are rich indeed. He sorted through all the census tables he had been able to find, compared statistical data across documents (number of residents, houses, and what not), and discovered inconsistencies. He wrote of the entire region, of springs and ravines, of the lives of villagers across the years, of the Pugachyov Rebellion, about the war years, what they ate, what diseases they had, and how many people died and when. He described how the residents of Ishutkino survived during the Volga famine of the 1920s, how the kolkhozes were established…

The 1921 Crop Failure

(From Chapter 1)

There was no rain during the entire summer of 1920. Winter crops did not sprout… Over the course of the spring and summer of 1921, not a drop of rain fell. All of the grasses and trees withered… This all led to a horrific famine. According to the stories of old-timers, everywhere you went the roads were filled with people on their last leg, some in a throng, others all alone. They were all in rags – women and children, or children on their own. People, standing beneath a window or in room, begged “for Christ’s sake,” or they sobbed, their eyes full of tears, pleading, “I haven’t eaten anything for three days, my young children are dying of hunger at home, please spare at least a crust of bread.” There were cases, and they were not rare, where people fell and died as they were walking along, and their corpses just lay there, not of use to anyone, tossed aside. My late mother-in-law, Maria Terentieva Fyodorova, recounted how a woman, all dressed in rags, with a small baby in her arms, overcome by hunger while walking to our village, fell down dead in the street and crushed her still living child.

A 1921 Labor and Defense Council report remarks:

From every direction one could hear the hungry cries of children. The Department of Public Education was surrounded by a crowd of hungry, half-dead children, who had been brought and left there by their half-dead parents, in the hope that the authorities would take pity on them. The financial department did not have funds to help anyone with anything… As a consequence of the famine, banditry increased. Peasants began to eat working livestock, completely ruining their livelihoods.

The disastrous years of 1921 and 1922 left peasant households without livestock… Here and there rumors of cannibalism were heard. To back these assertions up with facts, I consider it my duty to cite official documents that confirm these descriptions.

Buguruslan District Multistore

Consumer Society Food Department

3 May 1922

April 21 in the city of Buguruslan, the peasant family of Vasily D., from the village of Tolstoy, Bogorodskaya Volost, was brought and admitted to the hospital. It consisted of his wife Domna, 41, son Dmitry, 23, daughters Anna, 15, and Elizabeth, 4. The family was caught practicing cannibalism. Domna and her son Dmitry were luring children into their banya, slaughtering them and eating them. They also fed Anna and Elizabeth. There was a total of ten victims. Dmitry also stabbed his wife and ate her corpse. The Food Department has informed the Provincial Union of the above.

Chairman of the Board, Representative Ivanov

One more document:

To the administration of the Buguruslan Regional Multistore. Cons. Soc.

In our village of Staroye Semeykino, Baytuganovskaya Volost, mortality from hunger is continually increasing, all reserves of grain substitutes have been depleted, and people are feeding on the corpses of animals, eating all the cats and dogs. On April 18 a case of cannibalism was discovered. A citizen of our village slaughtered her four-year-old son; it attracted attention when it was noticed that she was cooking and eating meat; it turned out she was boiling the leg of her child, and the child’s headless, legless, armless body was found in a bag beneath the table. She died that very day. Her 11-year-old daughter survived her.

April 30, 1922. Sidorov, Head of Staroye Semeykino Feeding Station No. 31.

No one can read these lines without shuddering. Yet for the sake of historical justice, we must remember those horrific years and life back then with that of today.

Razeyev wanted to share the information he had collected, all the more so since he was confident of his facts. He decided to publish another book.

One thousand rubles from the priest, and a stay in a hostel from a fellow villager – this is the extent of the assistance that Lukich had received from others while working on his book. When asked why he did not ask residents or even the district for support in the collection of this information (which is actually a public good and beneficial to all), the retiree waves his hands, “What, go begging? Embarrassing. Somehow we managed on our own.”

Of course, Razeyev did not have money to publish the book himself. He could not afford an editor, proofreader, or layout artist. His daughter typed up the manuscript; a friend did the layout. For about a year and a half, daughter Yelena typed her father’s book every night after work. “Papa learned the computer, but it was hard for him to type, so I volunteered to help,” Yelena said. “Typing it, I learned a ton of interesting things about the village and our ancestors. Papa has completed a colossal piece of work!”

“When it came time to publish, I asked the district for support,” Razeyev said. “They didn’t give us any. So I printed 50 copies at my own expense. When it was all printed, I took an invoice to the region for 17,000 rubles, asking them to pay at least this. So much work, so many trips! They said they could not. They could only buy a copy of the book – at cost – for the library. And I said, ‘No, that won’t cut it.’

Better I give it out to relatives and sell it myself. I sold them for 500 rubles each. Some got purchased (one acquaintance, for example, took four books to Tolyatti), but mostly I gave them away, of course. Most people aren’t interested in the history of our village. For instance I was telling a neighbor, ‘All of your lineage is here, your forefathers and your forefather’s forefathers, your great, great, great…’ And he says, ‘What do I need that for?’ That’s how a lot of people felt. And they don’t want to buy a book; they’ll borrow it from a neighbor.”

No Reaction Whatsoever

It had been a long time since anything happened in Maloye Ishutkino. And the release of a book about the village and its residents was, without question, a signal event not just for the village, but for the district. Nevertheless, there was no presentation of the book in Ishutkino, nor was there any reaction to the book from district officials.

“I was invited to the district center to discuss the book, but somehow it never happened,” Razeyev said. “The head of the district archive said she would buy the book. I brought it to her and she says that her bookkeeping department said that I was required to give the book to them for free. Required! The Regional History Museum also didn’t want to purchase the book. Only the director of the regional library bought one. And, as to a presentation, I thought it would be really nice to gather people together and tell them about the book and the village. I even came up with the idea of a quiz for schoolchildren. Do you know the name of the ravine, the forest? So that the students at least would know something about their village. No one knows anything! But it’s all in my book! But they didn’t invite me, and I was hesitant to propose it myself. The only thing I did was agree with the head of the club on putting together a display on the history of the village. But that too hasn’t gotten off the ground.”

The local residents, according to Razeyev, reacted to the book “in different ways.”

“Not everyone liked it. And I even made some enemies,” he said sadly. “All because I wrote the truth, and, it turns out, we don’t like the truth here.”

Having said this, he fell silent and headed into his yard to chase his chickens back into their coop for the night. White chickens run to meet him, brushing up against his legs. Lukich drives the four purebred hens into the small hut, using a board as a ladder, saying “Let’s go dears, home now!”

The chickens take turns hopping up onto the board, and then into the hut.

“Oh, you are so good. Good night, now,” he said. Razeyev loves animals and is incapable of harming them. It is his wife Irina who has to slaughter them. She’s been doing it skillfully since she was young.

Irina slaughtered sheep, while the old men held them, and she drowns the kittens that the cats regularly give birth to. Razeyev managed to save one of the kittens and hide it from her. “Look,” he said, opening the door of a tiny house that stands next to the chicken coop. There, wrapped up in some rags, sleeps a kitten the size of the palm of your hand. “Momma will be here soon,” Razeyev says quietly, so as not to wake it, then closes the door.

Why this Gossip?

In the morning I walk around the village, polling those I meet about Razeyev’s book. A woman with a long braid is “up to speed” about the book but has not “managed to read it yet.” A woman with a plastic bag and some flowers also “heard of the book,” but has no interest in it. A man who cannot speak uses gestures to explain that he knows of the book, but had not read it, because he’s not interested in the village’s history.

I had almost reached the end of the street, but still had not met a single person that I could talk to about the book. Walking past the village club, which was shuttered and locked, I stood and stared at the memorial inscribed with the names of those who died in the Great Patriotic War, and those villagers who returned. It was erected thanks to Alexander Lukich’s efforts. He “dug up” the soldiers’ names and insisted that the village erect a memorial.

From Central Street I turn onto Zarechnaya. Ancient barns still stand in some yards, and some homes have ornately trimmed window frames. I knock on one door – no one is home. The only thing alive on this street are goats. At the far end, finally someone opens their door to me. A resident named Galina said she had read Lukich’s book and found it to be horrible. In her words, when the book came out, the village “was abuzz for two weeks.” People may have been reluctant to buy it, but what copies they had were passed from hand to hand: everyone was keen to read about their relatives. But after they read it, they were “choking with indignation,” she said.

“My momma bought the book in order to read about her ancestors. But what he put together was nothing but village gossip,” Galina said, outraged. “Who gave birth to whom, who gave themselves to whom, who didn’t… I don’t know about the village as a whole, but far from everything there is true. And it’s not just that it’s untrue – it’s nothing but malicious gossip. He upset my grandma: ‘she lived with this one, and from that one gave birth out of wedlock, and something else with yet another one.’ In reality, her husband died in the war, she had a daughter from him, and she died. And there isn’t a word about her! Then she was legally married, got divorced, then she got together with another man, this time without marriage. But he mixed the sour up with the fresh. After the war, we all understand, you had to have children with someone; they fined women who were childless, so of course women had children! And you had them with cripples, and with married men, with anyone, so long as you gave birth. There just weren’t enough men… But he didn’t write about himself… you just go and ask any family, and they’ll tell you everything. He didn’t ask permission to write about us. My sister had a child out of wedlock, and he wrote with whom and when, but he didn’t write anything about himself. He should be happy that our Aunt Polly died, or she would have given him a fistful of what for! Lots of people are indignant, lots. Why this gossip?”

“From the archives?”

“No it’s his. What sort of archive would write this stuff?”

“Well, they record place of birth, dates, marriages… So, you mean to say that you don’t have any sense of gratitude for his work, for the fact that he dug up information about your village, your family?”

“What sort of gratitude? No, absolutely not. I could do the same… I mean, what can you get in the archives that’s so special? Even I could take stuff from the internet.”

“Well, you didn’t go to the archives, but he did.”

“What he wrote about the history of the kolkhoz, of the party, they include that sort of thing in the district paper periodically… That’s what I think: the book is crap and that sort of thing should not be written.”

Another resident of the village who opened her door to me was also unhappy about Razeyev’s book.

“I didn’t read the entire book and didn’t buy it,” said retiree Tatyana. “First of all, it’s expensive. And second, why should I buy a book if I don’t agree with everything that is in it?”

“But if you didn’t read it, how do you know what it says?”

“Twice I got a hold of it through some acquaintances. I looked at bits and pieces of it, read about my people, about him, about a few others. Here’s the point. My son studied history, but he couldn’t find a job here. He too took an interest in our district’s history. I don’t know whose idea it was to write the book, but they started out together working on the history. Alyosha [her son] started working in the archives, but you know how it is working there: sometimes they demand money, sometimes you have to connect with someone over the internet… In short, he stopped going to the archives, but he and Lukich wanted to write the book together. But it turned out that Lukich collected gossip and wrote it all himself.”

“Why gossip? He found it all in the archives.”

“What sort of archival information did he have? Alyosha has far older data on the origins of our family. He searched on the internet… Did he tell you that my son should have been the co-author? He published the book, but only mentioned Alyosha in the introduction.”

“So what are you really upset about?”

“There’s some information there… That Nadya gave birth to a daughter out of wedlock. He wrote that. Yet he was silent about himself. Dirt on everyone else, but he offers no dirt on himself… And back in the old days they didn’t always do a formal marriage… Even today it is not always done. He didn’t get what he wrote about us right. Where did he get all this information?”

“In the archives.”

“Well, first of all, not all the archives survived. Second, he got information about our parents from the archives. But he did not, it seems to me, go very deeply into the past.”

“How do you mean? There is information about all the residents going back to the time of the village’s founding.”

“I would like to emphasize that I haven’t read the book. Why should I dig into things that I don’t agree with, if it’s not trustworthy? Alyosha said that this is incorrect, unreliable, distorted. The archives say one thing, but he has written something else. The same idea can be expressed with different words, and the meaning may change. So, if a person is not a specialist in this regard…”

Offended by the Truth

I report back to Alexander Lukich about my conversations with the dissatisfied residents. He gets upset.

“It’s a shame that I wrote a book for these people, and in the end, I created enemies. Some of them won’t even exchange hellos. I started this for my family, to search for my relatives. And then I thought, why don’t I look for information on others, they would surely like that! Everything in this book is written based on documents. There are some tales from old folks, but not about specific people. So it turns out I offended them with the truth. One person here says that I wrote about her husband, that he was born out of wedlock. But I didn’t make that up, here is the documentation! That’s what is written there. That’s it, I am the enemy. Another took offense that I wrote that she was born in prison. But I wrote about everyone just what I found in the archives. And they took offense! One even said she would sue me. But what did I do? I didn’t make anything up!”

As to Tamara’s son, Razeyev says that Alexei in fact did help him in the initial stages and found proof on the internet of the third census of 1762. “In truth, I did think of adding him as a co-author,” Razeyev said. “But I did a huge amount of work on this and covered all the expenses… For his contribution to the work I thanked him at the beginning, and I listed out what sort of information he obtained. I felt that was enough.”

Regarding the residents’ critique that Lukich hid facts about his own family, he said “I did not intentionally hide any facts. I wrote everything just as it was in the archives.”

It’s true: not everything in the chapter on the Razeyevs is “pleasant.” Lukich wrote about illegitimate children (“She gave birth to her illegitimate son Vladimir, fathered by Ilya Osipovich Fomin”), for example, and about suicides (“Life for my grandfather Fyodor Prokhorovich became unbearable due to constant discord with his son-in-law, and in 1964 or 1965 he hanged himself. I learned of this by telegram, but they did not allow me to take leave from my army unit to attend the funeral. This is how yet another branch of the Razeyev family line came to an end.”)

Among the residents of Maloye Ishutkino, there are some, however, who are grateful. Olga Burmistrova, the primary school teacher, said that as soon as the book came out, her husband, who was born in the village, immediately bought a copy.

“It is an awe-inspiring work,” Burmistrova said of the book. “I was fascinated to read it and could not tear myself away. When I read about my husband’s ancestors, I was able to imagine all these people. I have two children, and I told them all about them. It’s very unlikely we would have found so much information on our own! The local administration gave us our home. And we heard that some sort of wealthy people lived here once. And from the book we learned that these people were our distant relatives. As to people taking offense… Alexander Lukich wrote in such detail about everyone so that people could get a good sense of who they were. These were the sorts of things everyone in the village talked about among themselves, but when they read about it in a book, for some reason they were offended. Well, you can always find spiteful people; there will always be feuding.”

“These days I think, ‘What a fool, you didn’t need to write anything…” Lukich lamented. “Even the priest is upset at me, and that was for the first book.”

Unseemly Acts

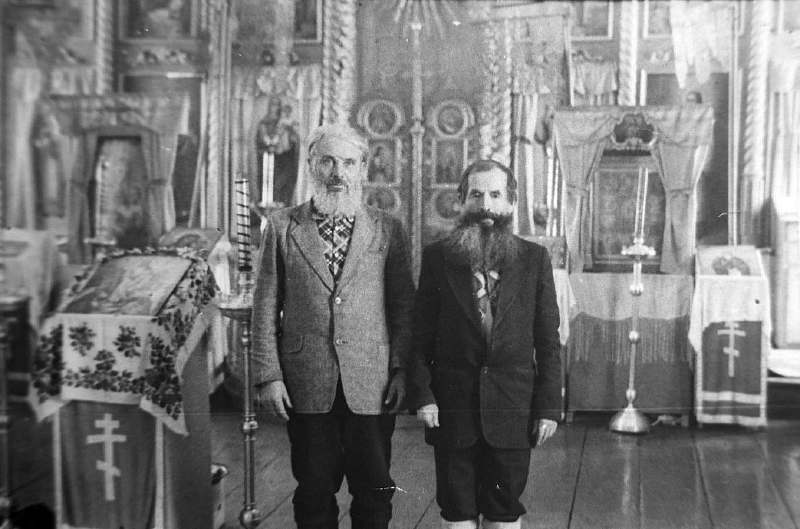

One of the most complete chapters of Lukich’s book is devoted to the church. He dug up the date and location of its founding, and the names and lifespans of all its priests. And he made a correction to something he had written in the first book about where their village church had been moved from.

“The old-timers recounted that the church was built in Shantala (a village in Shantala District) and then was transported the 34 kilometers here. That’s what I wrote. But it turns out that it was not Shantala! They took it from Stepnaya Shantala in Koshki District, which is much farther away!”

“In 2014, the church turned 100,” Razeyev said. “I tried to get the first book done before that date. I remember how the Volga Commune newspaper wrote about our church, that people refer to it as a “stolen” church. And I kept wondering, ‘Why?’ It turns out it was because some people initially wanted to build it somewhere else.

“In the repressive 1930s, they shut it down (I have all the documents) supposedly for being poorly maintained. And then the campaign started up to destroy churches. Some were turned into clubhouses, others were demolished. In our village they had a meeting to vote to shut down the church. And how did it go? Well they asked, ‘Who is against?’ Just try not voting in favor! I have a document with a list of all the villagers in favor of closing the church, and my father’s signature is there… In 1937 they decided to turn the church into a club (I have a copy of the budget, showing how many nails, how much water and lime, was needed to transform the building). And when they showed up to tear it down… We had this kolkhoz barn next door, with a thatched roof, and the people said, ‘Why tear it down? Let us store our grain there!’ And others tell how a woman went into the church with her baby and said, ‘Destroy it, but destroy me with it!’ In the end, they listened to the people and left the church standing. Grain was stored there until 1947, then they opened it back up. I have it all in the documents! The church survived, the only one in the district.”

Everything Lukich found in the archives about the church he gave to the priest. He proposed making a display near the entrance of the church, recounting its history. The priest, as he tells it, took the documents, copied them, but never produced the display. And when the first book came out with the old-timers’ tales, Father Oleg returned it to Lukich, saying, “I cannot accept this, it’s wrong to write such things!”

“That’s because of what I wrote about the previous priest,” Lukich explains. “Father Vladimir, who was fired for drunkenness. I wrote about that, and the priest said, ‘Why did you write about this? You shouldn’t write about such things.’ The whole village knew about it, but we should not write about it, everything should only be shown in rosy colors.”

Alexander Lukich pushes a stool up next to some shelves and gets down his drafts – the ones he wrote out by hand in the archives. Notebooks speckled with tiny, straight handwriting: tables, family names, certificates, letters, a sworn statement by a land surveyor, a hand-drawn map of the village showing homes… Among the papers: a 1990s complaint from residents of the village directed at Father Vladimir.

“It is described here in detail, why the residents insisted that he be removed from his post,” Lukich said, turning a page that has greyed with time as he reads aloud.

To the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, Alexei II. Father Vladimir is a non-believer. We wrote you about this, but you have taken no action. The metropolitan is not doing anything, because Father Vladimir gives him all the food he needs: meat, butter, potatoes, etc. He collected food from the residents of our district and shipped it out in vehicles.

Our people are good, conscientious and devoted to God. Our church suffered countless calamities under the communists, but the people did not let them destroy it. When Vladimir arrived here for his term of service, he replaced the entire old staff, adding others who believed in God just as much as he did. During his time of service and residency in our village, there has been no work done to renovate the church. Many people come to visit the church from outside, but there is nowhere for them to stay. Why not put up a building where they can stay the night? All around the church is rubbish, it’s such a shame. Why not build a lavatory? Why is there no bell tower? Why not update the church property?…

During his four years working at the church, Father Vladimir has not painted the church inside or out. Where is the revenue going, and who is watching over it? Other than Father Vladimir and the church warden Constantine, no one knows. Even the treasurer Ivan Larionov does not know, since he only presents receipts and expenses for signature: “I don’t do an audit, there is a bookkeeper in the next village where they take all the documents for bookkeeping. They keep it all secret.”

Father Vladimir never helps our believers, the needy, the aged, the crippled. But he does mind his personal affairs quite well. He buys one car after another. Just after the new year he drove up in a new Zhiguli… And over the past four years he has acquired everything: a VCR, color TV with an antenna higher than the church, a wall unit, a bedroom set, and also a palatial home in the neighboring village. There is even a place in Samara, where he goes on drinking binges. He drinks nonstop for four days at a stretch. He drank relentlessly at the Solovyovs in the village of Sosnovka, they could not supply him with vodka fast enough.

On December second, Father Vladimir did not even show up to hold service. He does not conduct the services properly; we villagers have been churchgoers all our lives – we know all the rites. Sometimes morning and evening services are not conducted. He hasn’t the time. He gets in his car with the church warden and goes off on his own business. Who doesn’t he have business with? He trades with the head of the kolkhoz, the agricultural council, the police chief, and the prosecutor. It wouldn’t be so sinful if he was using these connections to benefit the church…

You should have received the complaint that we sent over the signature of 30 villagers, but you have taken no action… People are driven from the church if they don’t acknowledge that they signed the complaint. After services, he doesn’t let people kiss the cross until he’s done interrogating them. Did you sign the complaint? No? If not, then they are allowed to kiss the cross. Those who signed are driven off.

There are many in the village with the last name Semyonov, and all have been interrogated. Zoya Semyonova was not involved in the complaint and fell ill after her interrogation. Ulyana Alexeyevna asked, “Am I going to the priest or the prosecutor for an interrogation?” And she stopped going to church. His behavior keeps many villagers from attending church…

He serves for himself, for his own profit, and leads a depraved lifestyle. It’s difficult to write about a priest like this, but we have seen and heard enough.

There was no service on Palm Sunday, since he was not here. He was drunk and in the neighboring village of Sosnovka. At another service, the church warden took all the money for the collection and put it in his pocket. It did not all fit, so he just carried the rest home in his hands. All of the villagers and passersby witnessed this. And Father Vladimir was nowhere to be seen that evening. He was drunk in the neighboring village, with his lover. In the morning he arrived around 10, puffy and hung over, somehow began the service, chasing an old woman into the church… Continuing the service, Father Vladimir started yelling at everyone, several times forcing the collection of donations. People gave two or three rubles and he yelled, “Why are you putting in so little? You need to give 25-50 rubles.” People were outraged – where is a pensioner to get such money? He completely lost all shame and conscience and purchased a Toyota.

We believers feel that there is no place for him in the Holy Church. We ask you to remove him from our church and also do an inventory and audit of its finances. And confiscate the things he acquired to benefit the church.

The true signature of the villagers…

“The priest did not like the fact that I included this information,” Razeyev explains. “In the previous edition I later crossed this all out, covered it up. And in the present edition I simply wrote that “he was removed for unseemly actions, and he left for Siberia.” I didn’t even attempt to give the priest a copy of this book. If you don’t like what I wrote, well… And this Father Vladimir, when they removed him, he burned all the documents, all the archives, out of anger. But the present priest has been here since 2000, and he is quite good.

The Grandkids Don’t Believe Me

Placing his hand on his book as if on a Bible, Alexander Lukich shares an idea.

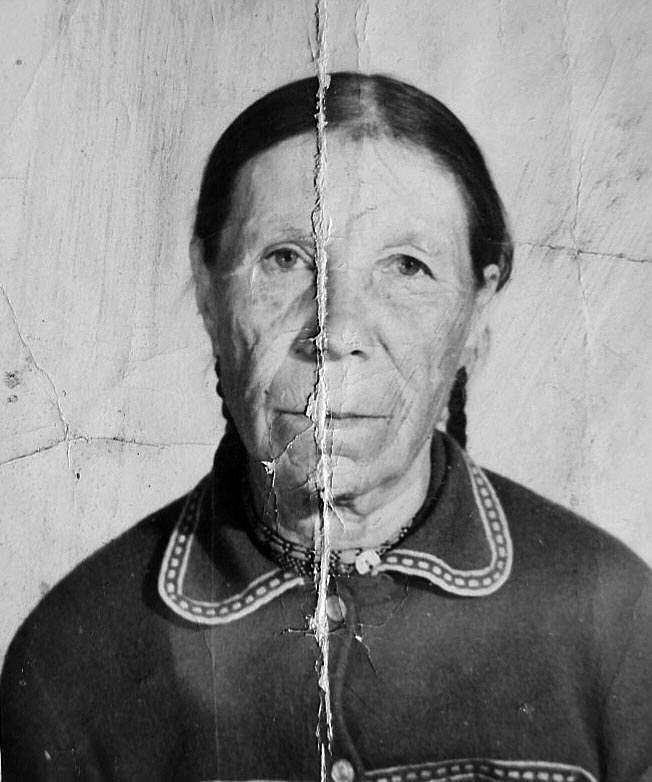

“I am considering writing a book about my life. For my grandchildren. Because these children don’t believe many of my and my wife’s tales. Say, how we starved during the war. My father died before I was even born. I know only that he felted boots and traveled from village to village. He was married to Vera from Malaya Mikushkina. Once, he went off to earn some extra money while his wife stayed at home. In Tatarstan he met my mother, Fekla and brought her home. His wife Vera was there: “How do you do!” And so Vera left…

“My mother and I were alone during the war and for a long time after. She was a cow herder her entire life, a very difficult type of labor, and there was nothing to eat. Those hungry childhood years left a deep impression in my soul; I can still see them. We lived near the mountains. In winter there was a sledding hill and the kids rode down it. But I sat at home and cried, because I could not go sledding with them – I had nothing to wear. I sat there naked. I cried and momma cried too. And there were these kolkhoz barns near our home for storing grain. And my mother went and took some grain sacks and sewed me a pair of pants. And I can still remember how she sewed and I kept urging her on, ‘Faster, momma!’ Today, my grandchildren don’t believe that I didn’t have any pants growing up. And my mother told me how, when she went off to work, she would leave me atop the stove, because there was no alternative: there was no daycare center.*

I was tied down, so that I did not fall from the stove. Just imagine, a tiny child all alone atop a stove! Or how she took just a tiny bit of grain for a week, grain by grain, so that she would have enough to bake bread. I remember how we were still walking around the yard in bare feet when the snow began to fall, digging up potatoes from the previous year. We ate grasses: borshchevik (hogweed), goutweed, nettle. And when I tell my grandkids all this, they say it’s all fairy tales. So I think it would be important, perhaps, to write such a book for them.”

So Many Questions

I ask Alexander Lukich to sign a release for use of his photographs in our publication. The retiree takes the paper and begins to print letter after letter surprisingly slowly.

“Do you always write so slowly?”

“Yes, I am rather old.”

I try to imagine Razeyev sitting at a desk in the archives and slowly transcribing hundreds of thousands of characters into his notebooks. I exclaim that it was an unbelievably impressive piece of work.

“In general, I didn’t find everything I needed about our village,” Lukich said. “I still have many questions! For example, I did not find out the exact date of our village’s founding.”

“According to the old-timers’ stories, the village of Ishutkino was formed in 1753, since that is when Ishutka Irbulatov appeared here. But I did not find any documents for 1753, only for 1762. In 1762 there was a census, the third census of the Russian population. And in that census I found the village of Ishutkino. All of the families are listed, including that of Ishutka Irbulatov. According to the second census, he was living in Penza Province. But after the Pugachyov Rebellion was put down, somewhere between 1775 and 1777, our Chuvash population moved away. In Samara I met a professor, a woman, who gave me an archival reference that shows that our village was mentioned as early as 1777. In other words, it was founded in the interval between 1775 and 1776.

“I went around the district asking this question, saying, ‘Let’s establish the official date of our village’s founding.’ I showed them the archival documents, and the director of the regional culture museum said that it was a complicated matter… So nothing came of it.”

Lukich said that he would really like to find the fourth census. He has the third and the fifth, but he was unable to find the fourth anywhere. “Lots of information remains to be found, there are many blank spots, questions from the Soviet era, and I also haven’t found out who this Ishutka was… I need to hunt for more details about the residents, but that means sitting in the archives again, digging, scrimping and saving on everything again…”

The retiree fusses about, showing me the pad where he has written which archival sections still need to be checked out, what information he needs to find.

“There is so much I haven’t found, but now, after this sort of reaction to the book by our residents, I don’t have the appetite for it. I don’t even know if I will go…”

Razeyev turns to look out the window. There are apple trees, the church cupola, hills, an empty road.

“The young people are leaving,” Lukich sighs. “Those who live here now are dying, and it is coming to an end. Soon, there will be no one left in the village.”

“But your book will remain,” I say.

“Yes, only the book will remain,” he agrees, falling silent.

Every day we write about the most pressing social problems in our country. Based on our experience, we are certain it is feasible to address and deal with them only by reporting the real state of affairs. This is why our team travels across the regions, takes interviews, talks to people and experts, does photo reportages to sportlight and document people’s lives and stories. We collect money for charity organisations without any commission on our part.

Our media exists due to donations. We hope you can consider subscribing for a monthly donation to support our project. Any help is valuable, especially if it is set on a regular basis. Any sum from you is an opportunity for us to plan our work.

Please, sign up to donate and sustain our media and cause.

Donate