To Serve is to Struggle

Last summer, the publication Takie Dela received a letter from the priest Mikhail Goncharov, who serves as rector at the Church of St. Nicholas in Antsiferovo, Krasnoyarsk Krai. The batyushka was writing from Yeniseysk Hospital, which he had been unable to get to for five months due to the impassability of the roads. He said he serves at the back end of nowhere, and it is impossible to get to the city to visit the doctor or for any other reason. He even finds it difficult to get to the neighboring villages he is supposed to serve.

In his letter, Goncharov asked for financial assistance to obtain parts for an ATV that he planned on cobbling together from old automotive parts. To his letter, Father Mikhail attached a photograph of St. Nicholas Church – dilapidated and by all appearances non-functioning. For 12 years the batyushka had been trying to renovate the church himself.

The author of this article posted the priest’s request to her personal Facebook page and within three days raised over half a million rubles ($8000) – enough to purchase a used Lesnik-M. The batyushka called the ATV “The Grace of God.” But a few days later he wrote to say that, after he purchased it, the locals had started to call him a swindler on the internet and accused him of “airing their dirty laundry in public,” and that some residents of Antsiferovo had stopped speaking to him.

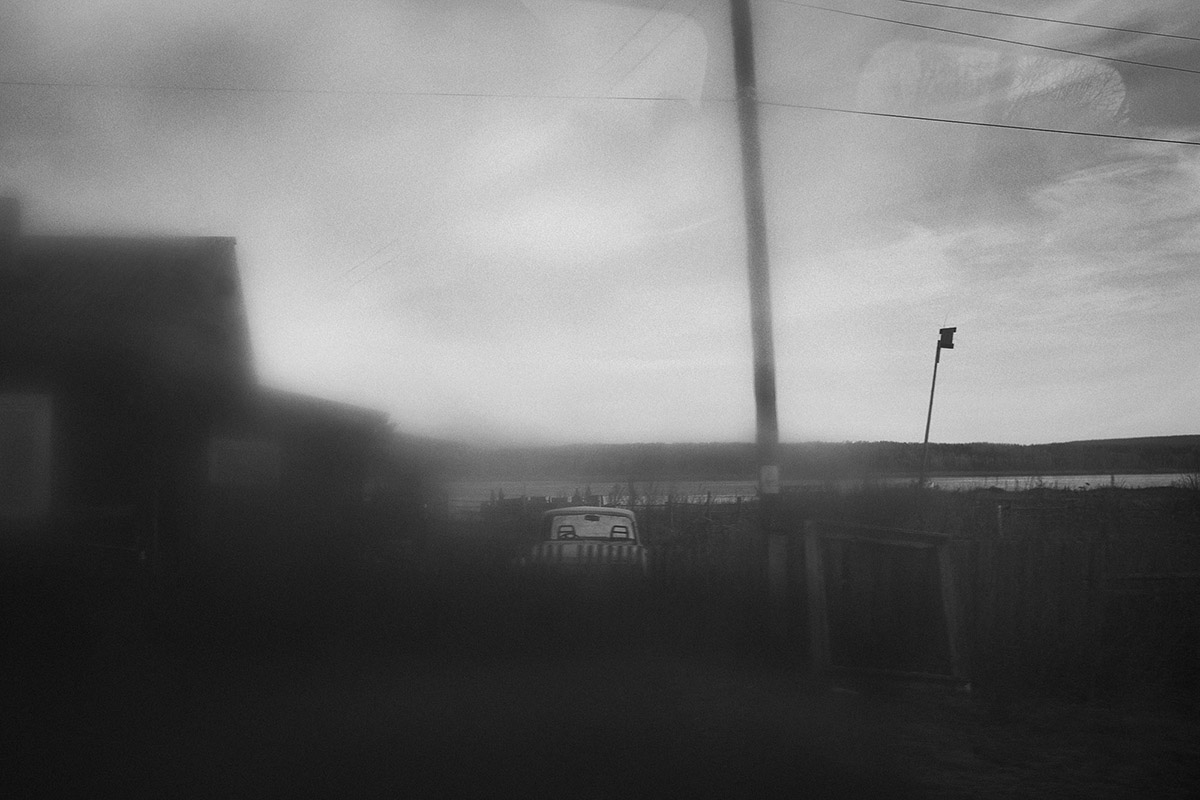

I decided to travel to Antsiferovo with a photographer to see first-hand how a village priest who needs to seek out God’s assistance via the internet lives and serves.

Riding atop a milk drum

No one can remember for certain if there was ever a road through these parts. The residents of Antsiferovo and other villages travel about on the zimnik in winter and by boat in summer. If the weather is dry, you can get around on a UAZ (one of the off-road vehicles produced by the Ulyanovsk Automotive Plant), but few are lucky enough to have one. During the mezhsezonye,[4] things grind to a halt, and nobody even tries to get to the city unless they’re desperate and manage to come up with the means. People stock up on food and medicine ahead of time.

It took an entire day to get from Moscow to Antsiferovo. First a long flight to Krasnoyarsk, then seven hours by bus to Yeniseysk, the seat of the Yeniseysk Eparchy, to which St. Nicholas belongs. From the eparchy offices Deacon Alexei Kornev – a friend of Father Michael – drives us in his car. After thirty miles, the road dead ends when it reaches the Yenisey.

This place is called Vyatkin Klyuch (“Vyatka’s Spring”), and it is where locals change from boats to cars and to drive to the city. Today there are two boats and a single empty car sitting there. Apparently, no one is worried about theft.

Father Mikhail is supposed to meet us at Vyatkin Klyuch – he does not have a functioning boat at the moment. It has been just a month since he purchased the Lesnik, but, according to Father Alexei, the “beast machine” has already helped Mikhail and other residents of the district out of many a difficult situation.

It is just 27 kilometers from Antsiferovo to the Klyuch, but we wait for a long time. And we hear the priest long before we see him on the horizon: the ATV creaks desperately, as if it is about to break down.

After coming to a stop, the 49-year-old priest jumps out of the cabin, greets us, and then dives under the vehicle. We catch occasional glimpses of boot-covered legs, a beard, an old, worn-out sweater. An exhausted Father Mikhail maneuvers back out from under the vehicle and, wiping his dirty hands, says uncertainly, “Let’s hope it won’t creak now. Let’s go!”

As he says goodbye, Father Alexei hands Goncharov a small package. “Put the prosfora somewhere your cat can’t get at it.”

“I’ve got a cat, Muska,” the batyushka explains. “He lives according to his own rules, and he may well steal.”

The ATV is not designed for passengers. Only the driver can sit fully upright, and you have to hunch to squeeze yourself into the back.

Father Mikhail starts up the Lesnik and warns us that the road may look scary, but there’s no cause for alarm – we will make it through.

The vehicle travels along the oozy shoreline, now and then dipping into the water. There is sticky muck and horrible ruts. It’s hard to believe any other car would be able to get through here. The ATV bounces along like a roller-coaster. It takes all our strength to hold onto the railings and the ceiling, and yet we still slam into the vehicle’s hard edges. The batyushka does not seem to register our discomfort. As he drives, his face lights up like a child’s who got a really cool car for his birthday.

“Five years ago, when the milk truck used to come here, it would even give the kids a ride to school,” the priest yells over the screeching of the ATV. (The dairy plant that Antsiferovo used to supply owes the local collective farm a lot of money, so Antsiferovo no longer does business with it.) “I myself have rode into the city atop a milk drum many a time when my car was broken down.

“At first, I had a Volga,” he says. “It was a reliable car, tough, but it needs a road. So when I hit a muddy patch, I’d stop and slice up logs with a chainsaw and use ‘pancakes’ to pave myself a road. And the locals would say, ‘We can’t get through on an off-roader and he gets through in a Volga!’ But I fixed up my Volga for roads like that. I secured the muffler to the bottom of the car so that it wouldn’t come off without taking the bottom and motor with it. I was constantly thinking of ways to make it super-capable, experimenting.

“Once, the Volga broke down while I was visiting the village of Chalbyshevo. They towed me to Lesosibirsk. The guys there always give me a good deal on repairs; they always show me true Christian charity. They towed me and my Volga in there, and a guy comes over and says, ‘Batyushka, why are you driving around in such an ancient vehicle? Let me give you the gift of a Niva.’[6] And so I started driving around in a Niva. It couldn’t handle the terrain and was constantly breaking down. I had to always carry a chainsaw, a blowtorch, and gas, so that I could start up a fire if necessary. Breaking down in the forest in winter is terrifying. There was that time two guys froze to death when it was minus 50: the heater in their car didn’t work well.”

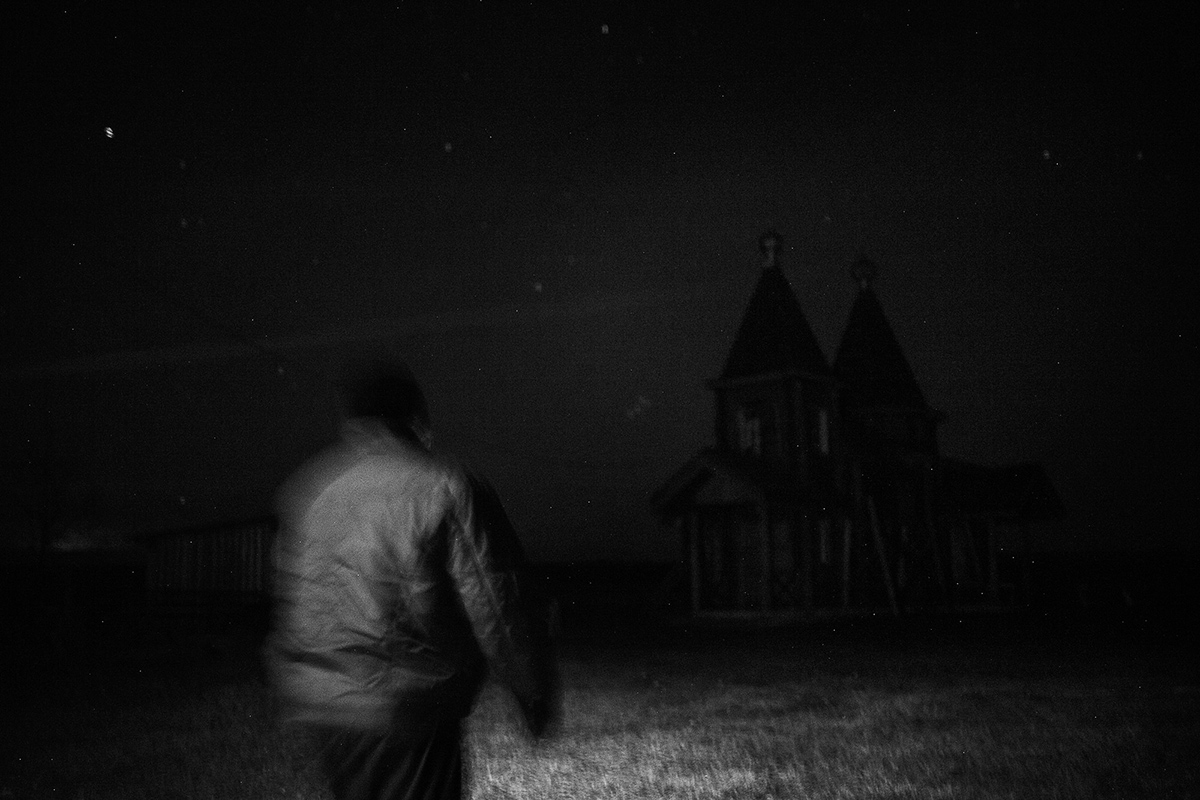

It was pitch black when, two and a half hours later, we arrived in Antsiferovo. The streets were lit only by the light spilling out of an occasional window. And it is a very small village – about 200 souls. There are two small stores offering basic goods at inflated prices, and a school, which only offers a few grades and has just 12 students. There is also a kindergarten with three kids and the kolkhoz “Ilyich’s Testaments,” dating back to the Soviet era (now, officially the Antsiferovo LLC). There is no hospital, so for serious emergencies an evacuation helicopter flies in; for all other medical needs, people visit the feldsher clinic.

Father Mikhail lives next to the church, his home separated from it by a small vegetable patch. In the moonlight, the church’s white walls gleam. Against one of them leans a large, wooden cross.

His house is constructed of wood with a large, fenced off shed attached, which houses Father Mikhail’s scrap-metal graveyard, filled with motors, and tools.

The home has two rooms and a small entryway/kitchen, which is where the stove is. Father Mikhail apologizes for the bachelorly disorder – “Matushka” (the standard form of address for a priest’s wife) Kapitolina has been ill and is staying in the city at her daughter’s for a month. She’s in no hurry to return. As the priest puts it, harsh rural life is not her thing.

Father Mikhail lives off the food from his garden and whatever comes his way. For his services, and sometimes just because, people bring him sour cream, eggs, fish, meat. Recently someone gave him a bream, and today the batyushka is baking it whole according to his favorite recipe. He sprinkles it generously with salt and places it into the oven.

Muska the cat is also having fish for dinner. The priest’s refrigerator is stuffed full of containers of small ruffes (a small, freshwater fish) “for cats.”

The meaning of life

Mikhail Goncharov was born in Krasnodar. He studied to be a mechanic, worked in a factory, then moved over into construction, doing finishing work on a small crew. It didn’t pay much, but he had enough to live on.

“The majority of our clients were well off,” he says. “Yet I saw their lives were hard. They had money, but they were not happy. They had to worry about their money. It had enslaved them. They could be called at any time day or night… and this brought them neither joy nor consolation. I didn’t want to live like them. I liked that me and the guys in our brigade were free. If we got tired, we chucked everything and hopped on the train for the mountains. The nature was beautiful there. Hiking, rock climbing… I really loved it.”

Back then, Mikhail was restless and spent a lot of time thinking about the meaning of life. And one day, as he puts it, “God led him to work for believers.”

Father Mikhail takes the bream from the oven, then gets the sour cream and bread. He places some incense on the stove and a sweet smell permeates the kitchen.

Goncharov says that he continued working for a time in construction after attending his first church service. While working on a job at a monastery in the Kuban, he became friends with a priest named Iriney. They spoke quite a lot, wrestling with spiritual questions. And they kept in touch after the work was completed.

Later, he was with some friends and found himself in a monastery in Krasnodar Krai. The church was under construction, and Goncharov noticed that the walls were being spackled incorrectly. He felt he could do it better.

After the service was over, he and his friends went up to talk to the priest, in order to pose some personal questions. Mikhail didn’t have any questions, he just tagged along. But after everyone had spoken, the batyushka turned to him and asked, “And what is troubling you?”

What was troubling Mikhail just then was the badly spackled walls.

“I offered to bring over some tools and show the guys how to do the walls beautifully, well, and without any extra cost. The batyushka frowned, called over a monk, and took him to task right in front of me, along the lines of: ‘Why aren’t you doing a good job?’ I was upset that someone got called on the carpet because of me. So I said to him, ‘Father, forgive me, I didn’t think this was how it would go. I simply wanted to help.’ And he said, ‘If you want, bring your tools.’ So I went home, got my things, and returned. I planned to stay for two weeks and wound up staying for nine years. At first, for four years, I was a worker, then became a novice. And then I saw that all sorts of intrigues plagued the monastery, which was bad. Orthodoxy and lies are incompatible. So I went to the batyushka and said this and that, there is this thing going on here, etc. And he started to try to convince me I was wrong… so I decided to leave. Truthfully, I had no idea where I would go.”

“You didn’t want to become a monk?”

“Monastery life is not for me. I wanted to have a family, to have little ones running around…”

So Mikhail decided to seek advice from Father Iriney, whom he had not seen for many years. He found Iriney in Yeniseysk, in a monastery, and spent some time with him there. And he might have gone from there to somewhere else, but while there he met Kapitolina, a girl who looked quite a bit like his first love.

“I realized that, if I didn’t marry her, I would regret it. And then Iriney told me that here, in the village of Antsiferovo, the Church of St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker needed to be restored, that the people needed to be guided, married, buried… He suggested that I move to the village, work in the church as a trudnik.[8] And I chose to stay.”

No income — no wages

In Antsiferovo, Mikhail was given a house that was half-fallen down. He got the stove working and spent the winter there. And then, along with two other trudniks, he undertook to renovate the church.

The building – constructed 240 years ago and neglected for the past 80 years – was in a terrible state.

“The last thing the church was used for was a shop and a storage facility,” Goncharov says. “When they abandoned it, one of the locals dug up the foundation. He was looking for gold, which, according to rumor, had been concealed there during construction. They didn’t find anything, but they did huge damage. There was no floor, no windows, and the ceiling was full of holes. There were just rafters instead of a ceiling, so I took them down and laid them on the floor. The roof was patched, and then the trudniks left and I was left all alone.

“Father Iriney said ‘Get married.’ So I called Kapitolina and said, ‘Well, I don’t know what will come of it, but I would like you to become my wife.’ She went silent, then said, ‘Well, I like you too.’ And that was that… She moved in with me. The bishop offered to have me ordained, first as a deacon, and then as a priest.

It had been assumed that Father Mikhail would have parishioners able to contribute toward bringing the church gradually back into decent shape. But nobody attended the dilapidated church.

Horses in the village of Antsiferovo.

“People lived for a long time without services, so why not live a bit longer without them?” Goncharov explains. “All the more, given that the church was in such a dilapidated state. To inspire someone’s first steps toward God, a church needs to have splendor. Aesthetics are important to people. And here there is nothing but disorder and cold.”

Father Mikhail turned to the local government for help restoring the church. They said they had no money and none was expected but that he should ask for help from the “krai” – that is the government of Krasnoyarsk Krai. Mikhail made inquiries, but, realizing that restoring the church promised to be a multi-year project, he got to work on his own.

As the first order of business, the batyushka used his own money to have a local mason put in a stove. He made the altar with his own hands. For this, as Father Alexei later told us, he “had his ears boxed” for messing with the architecture. The higher ups said something to the effect of “how dare you take these liberties without our knowledge.”

“Because the church is an architectural monument, you can’t just restore it on your own,” Goncharov explains. “But even if I had had the resources, I would still have done all I could on my own. Because, well, why do we need a monument? I made window frames, covered them with plastic, and installed them in the window openings. I bought icon lamps, found icons. And the church became more pleasant. Two or three people began coming to the church for services. I held out hope that there would be more people in future.”

But there weren’t.

Year after year, Mikhail’s requests for funding were met with the runaround by officials. After 12 years, the priest still hadn’t managed to attract a congregation. And he had to live on something, so Goncharov was forced to spend time making a living.

“A village priest doesn’t get a salary from the eparchy,” the batyushka explains. “His money comes from the congregation. No congregation, no money. Not for the church, not for myself. So I had to take up farming and look for all sorts of odd jobs. A wife and a daughter need to be fed. And it is really hard combining clerical duties with farming…”

The cabbie

For the most part, Goncharov made money through manual labor – crafting decorative window frames, chopping wood, plowing up a local babushka’s garden plot, repairing equipment. Sometimes he guarded the cow barn. But what he loved doing most was providing transportation services.

The locals were constantly asking him to take them to the city: one needed to go to the hospital, another wanted to visit relatives, yet another needed to buy medicine… People would also ask him to bring back food, construction material, equipment…

“If it were not for the driving, I don’t know how I would have survived,” the priest says. “And it would have been harder for the locals. They sometimes even asked me to deliver their mail from the city, because they don’t normally deliver it here. I remember back when I was driving the Niva, all of my pockets would be stuffed full of letters and money. My head was spinning: one person needed this sort of medicine, another needed another type; another person needed this food; another needed something else.”

“But why didn’t people do their own errands?”

“The people are poor; some are just making ends meet. Not everyone has the means to purchase the kinds of vehicles we need around here.”

“Do you charge for transportation?”

“I do, after all I have to fill the tank with gas. But you have to consider the need. If a child falls ill and has to get to the hospital, I’m not going to ask for money. And if someone can’t pay, of course I am not going to refuse them.”

“Your wrote that medical helicopters fly to the village. How often?”

“They do. But only for real emergencies. And, since we have a feldsher here, everyone goes to see her. She can, if the need arises, bring a child into the world. It’s happened.”

“And if, for example, someone needs a surgeon?”

“Then people look for a way to get to the city. For example, as I wrote you, for five months I was unable to get to see a doctor about my injured shoulder. After the spring floods, there was a ton of flotsam on the shores of the river – it was impossible to get through. And at the start of the summer a tractor driver and I used a bulldozer to clear fallen trees and brush – we made a road. But then all that washed away. The shore had turned into kasha. And I could not get to the doctor. And then my teeth began to ache beneath their fillings. It all became completely unbearable. With some difficulty I finally found a boat going to the city. But because of its schedule, I had to set things up so that I returned the same day. I couldn’t see both the doctor and the dentist in a single day, so I had to make a choice: heal my arm or my teeth. I chose my teeth. As for my arm, I only got to a surgeon in June, by which time it was in terrible shape.”

“If you feel compelled to do something bad, don’t do it.”

The next morning, we were able to tour Father Mikhail’s church and grounds. Near his home was the rusted out, wheelless Niva. In the garden was cabbage mixed with weeds. A chained dog whimpered in a broken-down greenhouse. Just a few years ago, it was home to various breeds of chicken, duck, geese, rabbit, cow, and pig… The villages residents would visit Mikhail and his wife as if on a tour.

“We lived well,” Father Mikhail says. “Nastya was little, and it was interesting and useful for her to grow up alongside animals. I showed her how chicks hatch, and she played with baby rabbits. I myself learned how to milk our cow Pestrushka, because Matushka didn’t like her. She just needed to wash the milk containers – my hands were too big to fit. Some things I enjoyed more, some things she did. And then both of us went crazy over guinea fowls. I tried to raise them, and bought an incubator. Once, the electricity went out for two days in the village (it happens often here), so, until the power came back on, I kept them warm on the stove. Still, when the time came, they did not hatch, since they’d been too cold. They didn’t have the strength. I remember I decided to crack open the eggs in order to see what was inside, and they were stirring and peeping.”

Because Father Mikhail was restoring the church, working on the side as a cabbie, and driving to lead services in neighboring villages, his farm gradually declined to nothing. The only animals that remained were the dog, a cat, and a long-haired piglet named Krasavchik (“Beauty”). There’s no internet to be had in the village, and the only place Goncharov can get a cell signal is in an outbuilding right next to Krasavchik. The batyushka jokes that the piglet emits wifi.

“I am trying not to get too attached to him,” the priest says about the piglet, “because sooner or later we are going to have to eat him.”

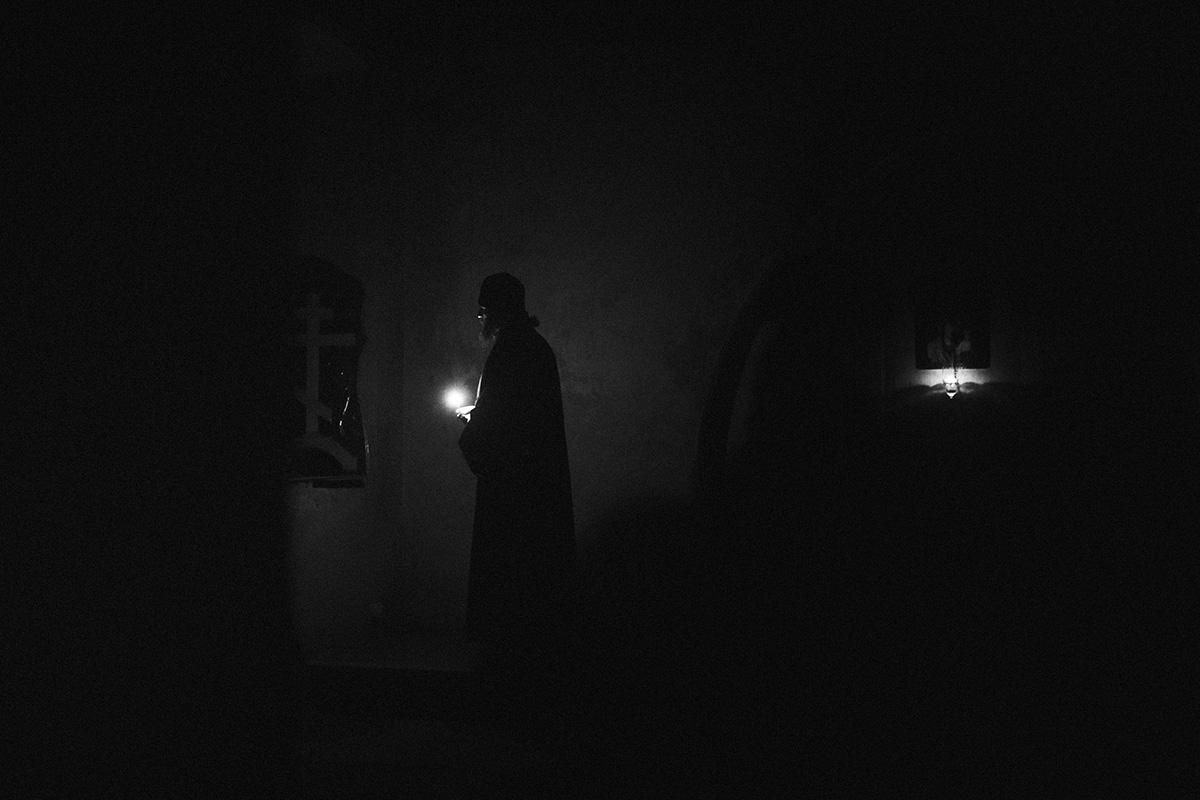

It is empty, dark, and cold inside the Antsiferovo church. To get to the central part of the building, you have to walk – as if across a bridge – on boards laid over gaps in flooring.

The batyushka lights the icon lamps and soon, out of the darkness, appear the Holy Doors (those at the center of the iconostasis), which he carved himself, two large stoves, and icons lining the wall. Our breath turns to steam, and we stomp from one foot to the other, burying our noses in our scarves. It’s difficult to imagine how anyone could endure a service in such cold.

“I conduct services here rarely, on major holidays,” Father Mikhail says. “In the winter, I warm up the stoves for a few hours before the service. Such a large space is difficult to heat. While I am feeding the stove, I am tired and sweaty. And it happens that no one even comes, and all the work is for nothing. The rest of the time I conduct services at home, near our stove – our door is always open to all.”

“Do people come?”

“Rarely.”

“Does that upset you?”

“No, it’s not about that. You can’t get upset. People just have to grow into it…”

“Maybe they simply don’t need a church?”

“They need it, they just don’t understand that yet.”

“What do they need it for?”

“The purpose of a church is that people think about God, that they work on their internal self, and to keep them away from any expression of Satanism… For example, from drunkenness. This is a huge problem here, almost the main cause of death. I wrack my brains thinking of ways to help people stop drinking. I’ve tried encouraging them to work, to help others. But, honestly, people don’t have any enthusiasm now. And there are gifted people here, people with taste, with skills. But since they don’t have any way to achieve anything, they drink. Once, I was working in the church, doing something or other, and Sanya came by and just sat silently, not asking anything. So I said, ‘Do you need something?’ ‘Nah,’ he answered. ‘Just wanted to sit. To think.’ So he sat and sat, then left. Then he came again, and again sat quietly for a long time. And then went on a binge. I later had to go somewhere, and then got the call: ‘Sanya hung himself.’ And he had been coming to me. He needed help. And apparently, I didn’t find the words for him…”

The batyushka says it is often difficult to find words when dealing with someone in a neighboring village who needs a priest’s help, but there is no way to drive there, and no way to phone them. Father Mikhail frequently sends text messages. Heart-to-heart talks are rare, occurring “by the will of God.”

One evening, driving home on his ATV, Father Mikhail saw a drunken guy walking along the banks of the river.

“So I stop and ask if everything is okay.”

“‘Yes,’ he says, ‘I argued with the ship’s captain and he put me ashore.’

“‘Do you need any help?’

“‘You could give me a lift to Lesosibirsk!’

“But I had a full load, and it was already dark. So I offered to bring him to Antsiferovo, where he could spend the night at my place, then we could figure out how to get him there. We chatted at home that night. It turned out he had received his draft notice. Mobilization, this and that. He sobered up at my place and said, ‘So they are sending us to Ukraine, and I am unbaptized.’ We talked till midnight, and he just couldn’t understand what to do about the draft notice. I baptized him and said, ‘If you feel compelled to do something bad, don’t do it. If you feel something is good, do it.’ I never saw him again.”

“Those who need it, they go.”

The next day, Father Mikhail suggests we explore the kolkhoz – the Antsiferovo LLC – and talk to the director, Sergei Sharobayev. Sergei is a regular at the church, supports the batyushka, and often helps out in difficult situations.

Antsiferovo stretches out along the Yenisey. The wide river impresses with its grandeur. The streets are clean. The homes along the riverbank are generally small and simple. The letters Z and V have been stuck onto the windowpanes, which are framed with write ruffled curtains. We even see these symbols, crafted it seems from painter’s tape, on the windows of tractors.

Here and there along the riverbank and in the streets we see broken-down equipment: rusting motorcycles, boats, trailers, cars.

Two men are puttering about near a rather large, covered boat on the riverbank. I ask them if they attend church services. The guys answer that the church was destroyed long ago.

“But they are holding services again.”

“Yeah, we don’t need any of that! We’re not believers. Anyway, half the village is Old Believers, so why would we need a church?”

The rest of the way to the kolkhoz we don’t meet a single soul. Antsiferovo looked like a ghost town.

The Antsiferovo LLC, which produces meat and dairy products, is the village’s only employer. It covers a large swath of land, has lots of equipment and vehicles, and has sheds filled with cows.

Sharobayev forbids us from photographing on kolkhoz property and refuses to have a picture taken of himself.

“If you take photos, then the adventures will start for me again,” he says.

Later, a local resident explains that Sharobayev asked the president an uncomfortable question either during a live broadcast or a write-in session.

“You know how it is. If you complain to the president, that complaint is passed down to the krai, and then here, and you find yourself in the doghouse. He [Sharobayev] supplies milk to the plant in the city. But the plant hasn’t paid him for years. That’s apparently what he asked about. And after that he was inundated with inspections and audits.”

According to Sharobayev, there is nothing in the kolkhoz or in the village to admire. Life in Antsiferovo has frozen in time, “having no road is a form of arm-twisting,” and selling anything they make, or even producing it, is very difficult. But, if you don’t work, you might as well lay down and die. And so Sharobayev works.

To the question of whether the village needs a church and a priest, Sharobayev answers without hesitation:

“Yes. Father Mikhail does a lot for the village’s spiritual life just by being here. He conducts services, and cleanses people’s minds. He pulls them out of the darkness.”

“So why does almost no one go to church, then?

“Think of it this way. How many people live in Krasnoyarsk? And how many churchgoers are there? And what is our population? It’s actually not such a small percentage of people who go to our church here. There are always four or five people from our village attending Paskha [Easter] services. I, for example, always go on holidays. Those who need it, they go.”

“Why do you think the church still hasn’t been restored after 12 years?”

“Father Mikhail, as far as I know, has been corresponding with the local administration for years, asking for help with the church. Five years ago, the governor gave, I believe, six million rubles [about $85,000] toward the restoration of the church. But to this day they are sitting on the village council ledger… There was one council head, now another… They simply pass this money back and forth and don’t do anything. No one pays Father Mikhail a salary; he has no support. How does he do this all alone? I remember I once asked him, ‘Father Mikhail, every normal person goes to the sea on vacation, to be in the sun. And you came here from Krasnodar… There are mosquitoes and gnats here. Have you forgotten all that while here?’”

“And what did he say?”

“He said he likes it here.”

Not wanting to speak to us any longer, Sharobayev introduced us to a couple, Svetlana and Alexander, who, he said, “go to church and will answer all your questions.”

“If there were a road, this wouldn’t be paradise.”

Some time ago, Svetlana and Alexander came here from the city to work. Alexander got a job as the school director, but is now retired. And almost nothing remains of the school.

“As far as teachers, there is one for history and one for math,” he says. “They come here for two days at a time, on Friday and Saturday. If the roads are bad or unpassable, they cannot come. Recently the batyushka gave them a lift here in his ATV. That’s it; now we have no idea when they will be here next.

Svetlana calls Antsiferovo a paradise that is hard to leave voluntarily.

“We have a vegetable garden, cats, and the view from the window is beautiful. You get up in the morning and the Yenisey is outside your window. There is a birch tree there, and once a year, on Pentecost, I tie a ribbon around it and give it a hug.”

When asked whether the village needs a church, Svetlana also answers without hesitation:“Absolutely!”

“And do you attend?”

“Myself, to be honest, I go rarely, on the major holidays. I can say that, for me, when it’s cold, or uncomfortable, it’s difficult. You need to think about God, but you’re thinking about your freezing toes… At first, he started up working there and people helped him. Then the badmouthing started… That he was asking for money for the church, that he started working as a driver… People thought that was a strange thing for a priest to be doing.”

“But, after all, he’s working as a driver in order to have something to live on. The eparchy doesn’t pay him a salary.”

“Yes, we get that. And people need what he does. Just recently a friend said, ‘We’re going to hire him to deliver some groceries.’ There’s no one else… People say that he might be drinking there in the church, partying. But that is just repeating gossip, I’ve not seen it. Not everyone says bad things about him. But a few spread rumors… And then, after he got the ATV, they started saying all sorts of nasty things… People started spreading dirt about him on the internet.”

“What did they say.”

“They said it would be better if they had given money for a road! Why did he write bad things about our village?”

“Why do you think people reacted like that?”

“Perhaps out of envy. No one here has had luck with anything, and then he pulled that off… And no matter how much people swore at him, he never says a bad word about anyone. We ourselves, perhaps, let him down, didn’t support him… Two or three people at a service is, of course, insulting to him.”

Svetlana and her husband tell stories about things that happened to them during mud season (mezhsezonye) on the road from Yeniseysk to Antsiferovo. Once, they got stuck and spent the night in their car. Another time, the roads were such an impassable kasha, they had to return to Yeniseysk and wait until winter. And then, after it froze up, the ruts were so bad that it took four hours to drive 17 kilometers.

To my observation that a road, obviously, is vital for residents of Antsiferovo, Svetlana philosophically muses: “If there were a road, this wouldn’t be paradise.”

The place for waiting

There are a number of villages and settlements around Antsiferovo with no priest. Father Mikhail does his best to meet their needs, but the distances are long, there are no roads, and sometimes there is nowhere to overnight.

Once, when the batyushka was leaving one such village by boat, his motor died in the middle of the Yenisey. He rowed to the shore and built a fire.

“I was just starting to warm up when it began raining. I carry a large sheet of plastic sheeting in the boat. It protects me well from the wind. I made a bed of it in the boat, lay down, covered myself, and lay there until morning. Then a passing boat picked me up.”

“Couldn’t you ask to stay with someone in the village? Why would you need to sleep in the boat…”

“I don’t feel comfortable putting people out. Once, I arrived for services in a village by car, driving my Volga down the ice road. And it broke down. The people who invited me asked me to stay at their home. But their grown children began to get upset. I begged their pardon again and again, but never stayed with them again. Before, if there was no priest in a village, and people wanted a service, a funeral, or a baptism, they invited the batyushka and then went and picked him up themselves. Gave him a ride there and back. But I have to get there on my own. And there is the sense that people are sick and tired of me.”

On Saturday, Father Mikhail gets up before sunrise to get the household chores done and prepare for Sunday services in Nazimovo. He fills his thermos with coffee, gets out his warm work coat and gloves. And carefully rolls up his cassock, sub-cassock and stole. He then puts everything into a large sport bag.

“Nazimovo, Novonazimovo, and Yartsevo are where I go most often. Less frequently to Ust-Pit. It’s a 200-kilometer drive to Yartsevo; 110 to Nazimovo. No roads. The ATV is a godsend.”

Nazimovo is a small village, but the locals recently built a church there on their own. There is a small congregation, so they pay the batyushka for the service. But the main thing is that they are eager to see him. When the rivers are open, Father Mikhail travels by Meteor (a passenger boat), but in the mezhsezonye he travels by motorboat.

“I go there once a month, sometimes every other week. Tomorrow, as it happens, I need to lead a service in Nazimovo. I arranged for Lyoshka Malkov [a resident of Antsiferovo] to take us there by motorboat. It’s an open boat and will be very cold. But not to worry, we’ll dress warmly and, if God wills it, we won’t freeze to death.”

We put on every bit of clothing we have: work coats over down jackets; huge, ugly gloves over our mittens. It’s a three-hour ride to Nazimovo, and the wind is fierce.

The batyushka sits up front and periodically turns around, to check that we have not turned to ice. The entire way he covers his right ear with his hand – it’s been bothering him for a long time, but he hasn’t managed to get to the city to see the ear, nose, and throat doctor.

“The batyushka situation is tough.”

In Nazimovo we are greeted by Natalya Kolmykova, a talkative, friendly local woman who works at the local weather station. She is sincerely happy that Father Mikhail has come and proudly recounts how little Nazimovo managed to get its church.

“Where the church stands now there used to be an old club, and before the club it was a church [demolished in 1939]. The club burned down, so the lot stood empty. And the feds allocated money for some sort of modular club to be put up in place of the old one. But there’s no one but us pensioners here, so what do we need a club for ? Well, that’s my personal opinion… And so we came to the meeting and said that we only wanted to see a church on the church plot. And the village head said, ‘If you don’t vote for a club, then you won’t get one. And you also won’t get a church – who’s going to build it? And even if you build it, you’ll shut it down and no one will ever go there – and it’s very expensive.’ And he was right, of course… They made us a heated floor there [in the church]. We paid 10k once, but now we don’t even turn it on… In general, everyone voted, and they voted for a church. And they sent the club to Antsiferovo. And so they are happy and we are as well.”

As Natalia told it, by lucky happenstance a new head of local government was election at that very time, and he had “rich friends in Moscow.” They would come to Nazimovo on vacation and, when they found out about the church, they helped get it built.

“One guy donated timber for the church. And some guys built it. We went around the village, collecting money for the builders. And then the whole village took part in the caulking, the cleaning, the painting… People contributed as much as they could. We really wanted a church, and through God’s grace it all came together.”

But after they built the church, the question arose: where are we going to get a batyushka?

“The batyushka situation is tough. There aren’t any in the eparchy. And our community is small: just five, maybe seven, attend church, and there’s no money. We can’t afford a batyushka, can’t support him. And there is no work here for him. So we agreed with Father Mikhail that he would come to us occasionally. And we are so glad when he does! When the rivers are open, we buy him round-trip tickets and pay him a little stipend. We toss a bit from our pensions into the common pot.”

Together with Father Mikhail, we overnight at Natalya’s and go to the church early in the morning, to get ready for the service.

The church smells of freshly-cut wood. The floor tiles in the vestibule are as cold as ice. To the left is a small stove. After starting it up, the batyushka disappears behind the altar, to get ready for the liturgy.

The parishioners trickle in. There are five today, two young women, the rest a bit older. Father Mikhail, having changed into his vestments, and encouraged by the parishioners, seems like a different person. He is clearly a bit nervous, but only during the sermon does his weariness show through – the trip there and the nearly sleepless night have taken their toll.

Immediately after the service, a man enters the church. His relative has died and needs a funeral. Everyone in the church whispers to one another: it is as if the old woman purposely held out until the priest’s arrival.

After the funeral, it is time for our return trip. But Alexei, who ferried us to Nazimovo, spent the night here with relatives, and was “whooping it up” into the wee hours. So he is in no condition to drive the boat.

The batyushka takes the helm. And at various points along the way he says a prayer – at all the spots where his motor has broken down. He explains that the Yenisey is treacherous. One summer, his neighbors Vika and Vasily tried to get to the city by boat, but they drowned, and their three children were saved by a passing boat.

About halfway through the return trip, the priest points out a dark spot on the right bank of the river. It is the cloister where Father Iriney lives now. The monk remains one of Father Mikhail’s closest friends. And when things get particularly difficult, he comes here to have a talk with him.

“If i am not on the right path, lord, show me the way.”

We make it back to Antsiferovo without incident. As we approach the Church of St. Nicholas, we see two men walking around it, examining something. They are restorers who have come for the first time to evaluate how best to attack the work ahead. The money that the regional administration allocated to the church will be used to restore it back to what it was “in better times.” But even that is cause for rejoicing for Father Mikhail: finally, there is some movement!

“Now they will patch the roof and the foundation, so that time does not further damage the church. I’ve been waiting for this for so long! In order that the administration undertake restoration, the building needed to be on their balance sheet. And doing that required me to do a lot of legal paperwork to make the parish official. It took a bunch of documents and time. I had to find enough people to agree to be listed as parishioners. They signed, and we sent in their personal information. It took a long time to arrange it all… and now we will wait for them to issue the money for restoration…”

“Don’t you worry it could drag on another five years?”

“I have made enough noise that it would be difficult to stop things now. I don’t think it has been in vain. The main thing is to remain here. If I leave, everything will be lost, nothing would be restored.”

“But does staying make sense? Maybe it would be better for you to go where there is a ‘living’ church, a parish?… or to the city?”

“Well, my wife would like to live in the city… Of course we could live there. But why? I would be the third or fourth priest there. I think it is important to try to do something here.”

“Don’t you want to live more comfortably?”

“It’s not important where you live. It’s important how you relate to whatever surrounds you. You can live in harmony in a hovel. And you can live in a mansion but want to hang yourself.”

“You don’t feel abandoned in Antsiferovo?”

“You defeat the road by walking it. I need to keep scrambling. If I am not on the right path, Lord, show me the way.”

In the evening, after feeding himself and Muska, the batushka sits down near his stove and tells us that he dreams of a small wooden church like the one in Nazimovo. So that, while he is busy corresponding with the bureaucrats, searching for money for restoration, the residents of the village could attend church in a warm and comfortable place. And the parish would gradually grow. Father Mikhail is absolutely certain that a church – be it cold or warm, small or large – could never be unnecessary.

“I believe that a church could change everything. I want there to be a parish, perhaps not large, but strong and stable. So that there is a community. So that after church people will drink tea and have a meal together, discuss this or that question or problem. If a babushka needs her garden turned over or her roof fixed, they would discuss it and help her out. Like that. So that there would be mutual aid. The village would be such a wonderful idyll.”

Where he will find the money for this, Father Mikhail has no idea. But he has figured out how to build a church for not very much money. And is ready to take on the work himself.

Living without a salary is of course difficult for Goncharov. But, as he put it, there are pluses. For one, freedom.

“If a priest is paid a salary somewhere, he has to do certain things in response. In that regard, I am free. There is plenty in the church that has no relation to Christianity. I have a hard life here and would not want to have to conduct various events, for example antiterrorist ones, to be distracted by them. To install a security camera or whole security system… Or, for example, I get a letter from the eparchy, ‘How do you solve the problem of the disposal of solid household waste?’ What the bleep is that? So I call others and ask them how they solve this? In the end, I wrote that I don’t have any solid household waste, that I burn it all in the stove… I don’t have a salary, but I can’t say that I don’t have any money. The Lord does not forsake me.”

“Did your relationships with the other people in the village truly suffer after you got the ATV?”

“They showed me some comments on the internet, that I was a swindler… Stuff like that…”

“How does that make you feel?”

“I just have to keep doing my job. Christ wasn’t able to please everyone, and they said plenty of nasty things about him, so why should I worry about what they say about me? A few people stopped saying hello me, but what can I do? I have to live the way I live. I don’t consider these people bad. It is their weakness. And I have plenty of my own weaknesses…”

“Do you feel like you belong?”

“Not always. But I don’t trust my feelings. If this or that thought arises, I can talk to Father Iriney about it. But my life, as before, I see as in service of God. If I serve him, he will not forsake me. And he will work miracles, like the ATV for example.”

“You are dishonoring the entire village!”

We had planned to leave the village the next morning. We awoke early, in order to take the ATV to the zimnik, to see the road. But on the zimnik the ATV breaks down – the rear axle falls off. And this is a big problem, because there is no other way to get out of the village.

Carefully, on just the front axle, the batyushka gets the ATV home. He assures us, “I’ll just fix it, we’ll drive carefully, and everything will be fine.”

But at home there is a new problem. The builders who are working to preserve the church have knocked the huge cross to the ground and left the gates to Goncharov’s garden open. Cows have gotten in, broken down the fence, and eaten almost all of his cabbage. After driving off the cows, Father Mikhail goes to the village administration and asks them to tell the builders not to leave the gate wide open. And then the feldsher, who happens to be passing by, pounces on him.

“You are dishonoring the entire village with your fence,” she yells. “Guests come to visit and they laugh at your house! How can a priest live in such a mess?”

Goncharov silently turns away and goes to lift up the cross and fix the ATV.

“Everything is just fine”

There is no guarantee that we will get to Yeniseysk today. But there is also no other option. Antsiferovo resident Irina is going to the city with us. She has had a toothache for four days, and the ATV is the only way she can get to the doctor.

We drive slowly, but after 30 minutes the Lesnik dies and will not restart. There is no phone reception. And going by foot through the mud and ruts is not an option. Father Mikhail gets up onto the roof of the ATV, holds his phone up to the sky and tries to get a connection. And then, as if by a miracle, a boat appears – kolkhoz worker Oleg is heading to the village.

We wave frantically, and the boat approaches the shore. Oleg cannot take us to the city, so the only option is to return to the village with him. Journalist and photographer are crestfallen (the plane will fly to Moscow without us), and Irina, pressing on her sore tooth through her cheek, is all but in tears.

Father Mikhail looks out at the water for a long time, and then suddenly says, “In their comments, people wrote that I was dishonoring the village by speaking ill of it. That I was lying, because ‘everything is fine with us.’ And yet we cannot right now go to the hospital. And it is not clear how or when Ira will get there. And so is everything fine with us, really?”

“Yes, we have constant problems here,” Irina chimes in. “I gave birth to my third child at home, because the medical helicopter didn’t come that day. The feldsher delivered my child. Three women have given birth that way here… And in the hospital later they yelled at me, saying I shouldn’t give birth at home. But what am I to do if I can’t get there? After Father Mikhail’s letters, at least the village council got a car. They have a car, but they don’t take anyone in it. They always have excuses: either ‘you’ll get too many groceries in the city,’ or ‘we don’t take children,’ or something else. But Father Mikhail takes everyone, doesn’t refuse anyone! Thanks to him, we are surviving here. ‘Father Mikhail, we need to get a refrigerator!’ And he hauls that refrigerator on top of his passenger car with them inside. And then these same people find fault with him!”

We go ashore and stand about feeling at a loss. The batyushka runs off to find a boat: Who knows? Maybe someone will agree to take us to Vyatkin Klyuch.

Irina shifts from one foot to the other. She is worried that she will not get to the hospital today.

Twenty minutes later Father Mikhail runs up all in a lather. Only Sergei Sharobayev agrees to help us get to the city; He’s ready to have his worker drive us. But neither the batyushka nor Irina will be taken, just the journalist and photographer. Goncharov is upset (he had planned to finally see the ear doctor), but he does not beg for himself. He begs for Irina, who is on the verge of crying. Sharobayev takes pity on the woman.

Where there is a church, there will be life.

At Vyatkin Klyuch, frozen to death by the wind, we transfer into Father Alexei’s car. He reassures us:

“We’ll tow and fix his ATV, don’t worry.”

We share our impressions of our trip with Father Alexei. And we ask how it is that a priest is invited to serve in a broken-down church and no one helps him.

“That’s just what a priest’s service is like,” Father Alexei explains. “Honestly, if it were up to me, I would have gone even farther into the sticks.”

“But how is he supposed to create a parish there?”

“By doing what he’s doing. By serving bit by bit. Light a little spark here, a little there. The people will come.”

“People say that it’s cold and uncomfortable in the church…”

“The idea that people want a church that is warm and beautiful is an excuse. Why should the priest be the one to light your stove? Come and fire it up yourselves, help out. The priest should deal with the parish, with his immediate duties.”

“Couldn’t the eparchy help?”

“How? It’s poor. To serve is to struggle. If there is a parish, there will be a salary. No parish, no salary. The eparchy can donate wine for the service, and that’s it… That’s how it is everywhere, all over the country. The eparchy has to pay taxes to the state. Father Mikhail reports he has nothing to contribute, because he has no funds. People settle up with him in milk and fish, so how can he write that down in his report? Now even the patriarch has blessed the idea of priests having jobs. Work during the week, and serve on weekends. But, according to the rules, a priest should not keep livestock or a garden, he should only serve. Otherwise, your farmwork interferes with your service. I have problems with money myself, and so I have gotten a job. I have three young children; they have plenty of needs.”

“How did the eparchy feel about Father Mikhail asking people for an ATV?”

“Good! He’s great, and at least he can come to visit us now. We have meetings, but he couldn’t get out…”

“Father Mikhail told us he fears leaving. That without him the village would die.”

“That’s all true. Where there is no church, a place dies. And where there is a church, there will be life.”

We don’t talk with Father Alexei for the rest of the trip. I recall how, before we got into the boat, I warned Father Mikhail that, quite possibly, after this article appeared, people would rise up against him again.

And Father Mikhail answered, “If something good follows this, if something gets stirred up, I am ready for it.”

В материале используются ссылки на публикации соцсетей Instagram и Facebook, а также упоминаются их названия. Эти веб-ресурсы принадлежат компании Meta Platforms Inc. — она признана в России экстремистской организацией и запрещена.

Every day we write about the most pressing social problems in our country. Based on our experience, we are certain it is feasible to address and deal with them only by reporting the real state of affairs. This is why our team travels across the regions, takes interviews, talks to people and experts, does photo reportages to sportlight and document people’s lives and stories. We collect money for charity organisations without any commission on our part.

Our media exists due to donations. We hope you can consider subscribing for a monthly donation to support our project. Any help is valuable, especially if it is set on a regular basis. Any sum from you is an opportunity for us to plan our work.

Please, sign up to donate and sustain our media and cause.

Donate